Recapping the 2024 growing season and looking ahead to 2025

If we were to look at the records of planting date and weather from 2024 without knowing the yields, we might not guess that corn yield beat and soybean tied previous yield records for Illinois. Here, we’ll take a quick look at the 2024 growing season, and consider whether we might apply lessons from it as we manage crops in 2025.

Growing season weather and crop conditions

Illinois weather was on its usual rollercoaster in 2024: February was dry, and March was very warm with below-normal rainfall in most of Illinois. This had conditions favorable for early planting: by April 1, 1% of both corn and soybean crops had been planted, and 2% of both crops were planted by April 8. April brought rain that slowed planting progress: both crops were at about 27-28% planted by the end of April, which was below normal for corn and above normal for soybeans. Rain in early May brought some further delays in places. By May 15, about half of the acreage of both crops was planted, which was well below normal for corn and about normal for soybeans. Planting wrapped up on a normal pace, ending the second week of June, later than normal for corn and a little ahead of normal for soybeans.

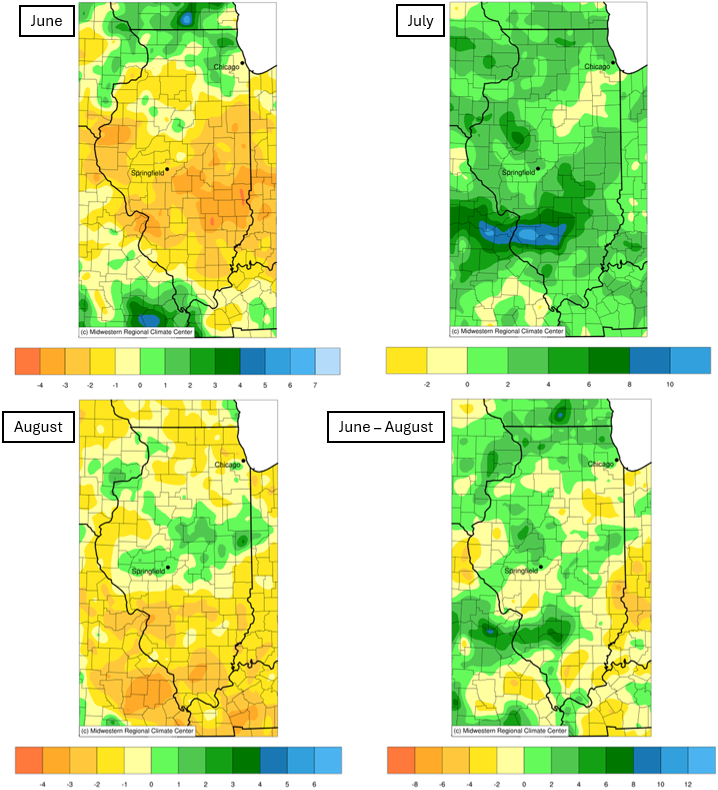

June was exceptionally dry, with most of the state experiencing rainfall deficits ranging from less than an inch to more than 3 inches (Figure 1). By mid-June, signs of water stress were visible in fields in the drier areas. This is similar to what we saw in June of both 2022 and 2023, and highlights the fact that stress like this, accompanied (as it usually is) by high amounts of sunlight and good development of roots deeper in the soil, can be positive for the corn crop, as long as the stress gets relieved before pollination. June was also very warm, continuing the trend that started in May. Warm temperatures are good for crop development, as long as there is enough water for good leaf expansion.

The dryness coming out of June was relieved by rainfall in the first week of July, which set the corn crop up for reasonably successful pollination. Remnants of Hurricane Beryl brought much more rain to eastern-southeastern Illinois on July 10-11; July rainfall totals ranged from 2 to 8 inches above normal, and more than 12 inches of rain fell in some places. July temperatures were below normal as well. These conditions increased corn and soybean crop condition ratings to some 70% good+excellent. It’s not unusual for July rain to increase crop conditions, but in 2023, crop ratings had fallen to near-record lows during dry weather in June, and they didn’t recover until August. Even then, they ended up lower than ratings associated with yields as high as those in 2023.

Average monthly air temperatures were 2 to 5.5 degrees above normal between April and June, leading to an early start to the reproductive stages for April-planted corn and soybeans. By July 1, the USDA-NASS reported that 17% of corn had reached the silking stage, well ahead of the 5-year average of 3%, while 25% of soybeans were flowering, compared to the 5-year average of 10%. In those fields, however, rainfall arrived after corn pollination began, with the lack of available water before the rainfall contributing to “tip-back,” where kernels failed to develop at the tip of the cob (Figure 2). In addition, early-planted soybeans did not develop leaf area and grow as rapidly in June as they might have with better soil moisture. That may have had little effect, however, since soybean growth in July and August can (and, in 2024, did) make up for a slow start.

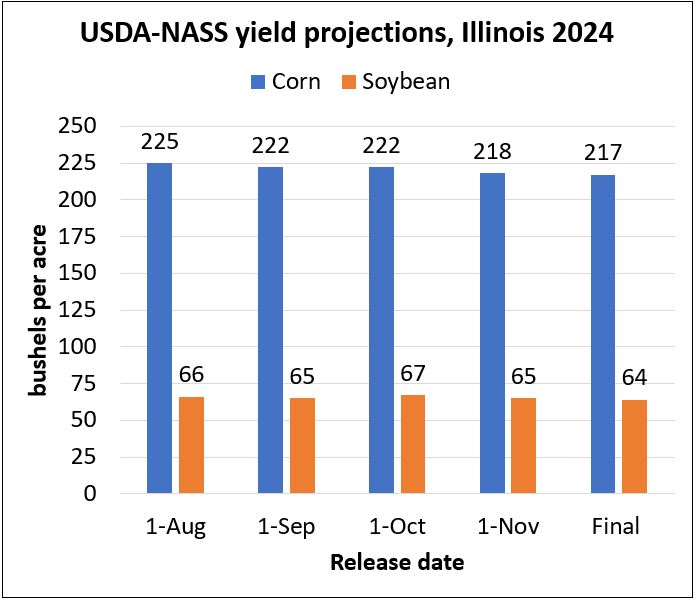

The wet trend and generally normal temperatures continued throughout most of August and provided good conditions during the grain-filling period, reflected by the USDA-NASS yield projections throughout fall (Figure 3). Higher-than-normal temperatures in September also led to rapidly drying crops, allowing many producers to begin harvesting earlier than usual. By the end of September, 21% of the corn and 24% of the soybean were harvested—compared to the 5-year average of 16% for corn and 11% for soybeans.

New state record for corn

Despite the slow start to corn planting and the variable weather, Illinois corn yields set a new record of 217 bushels per acre in 2024, beating the yield of 214 bushels per acre in 2022. The USDA-NASS August 1 estimate was 225 bushels per acre (Figure 3); the drop in estimated yield may have come from high kernel count, with perhaps some loss of kernels to abortion, and maybe some kernels that ended up a little lighter in weight than expected due to very dry conditions in September. Both would have affected last-planted corn the most.

While dry conditions around pollination reduced kernel number in early-planted fields, these fields benefitted from favorable conditions during grain-filling in late August and early September, likely resulting in heavier-than-normal kernels. Modern corn hybrids have a functional stay-green trait that maintains leaf photosynthesis during grain-filling, and it was not unusual to see fields with healthy canopies with dark green leaves until close to physiological maturity (Figure 2). On the other hand, late-plated fields may have benefitted from better moisture during pollination and achieved near-normal kernel numbers, but were under stress during the critical grain-filling period, which ultimately impacted final kernel weight.

Soybeans matched the previous yield record

The USDA-NASS projections were fairly stable throughout the fall, decreasing from 66 bushels per acre in August to 65 bushels per acre in November. This would have set a new state record, but the final yield (January) dropped to 64 bushels per acre. It is reasonable to assume that the very dry conditions in September also contributed to the estimated yield drop in soybeans. As discussed above, the planting season had a long tail, with only about 80% of the soybean crop planted by May 31, placing podfilling periods under some stress in late-planted fields.

Early (April) planting significantly boosted soybean yields, at least in some areas of Illinois. This was probably due to faster development in June, earlier flowering, and earlier maturity, which allowed podfilling to be completed before soils dried out in September. In a planting date trial in Pike County (western Illinois), a maturity group 3.6 variety lost 6 bushels from April 9 (yield 87 bu/ac) to April 30, another 12 bushels from April 30 to May 18, and 19 more bushels from May 18 to June 3. This resulted in a yield loss of approximately 0.3 bushels per acre per day in April and 1 bushels per acre per day of planting delay in May, with the earliest planting yielding 37 bushels more than the latest planting. At a site in Warren County, the same variety gained 3 bushels per acre from April 12 to May 6 (yield of 70 bu/ac), lost only 1 bushel from May 6 to May 20, then lost 10 bushels from May 20 to June 7. The overall yield loss from earliest to latest planting was only 8 bushels per acre, or roughly 1 bushel per week of delay. While planting in April remains a goal for both crops, we can expect the yield penalty from planting delays to range widely, mostly because the in-season weather has so much influence on yields.

Crop yield trends in Illinois

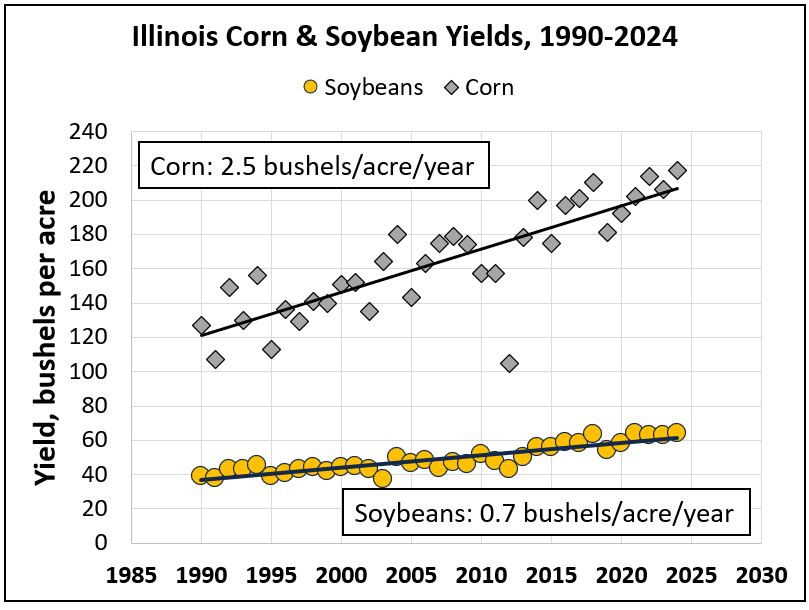

Figure 4 shows the yield trends for corn and soybeans in Illinois from 1990 through 2024. During this period, corn yields increased by 2.53 bushels per acre per year, while soybean yields increased by 0.72 bushels per acre per year. Based on the trendline (solid lines in Figure 4), corn yields first achieved 150 bushels per acre in 2002 and 200 bushels per acre 20 years later (2022). In the case of soybeans, it took 13 years to increase yields from 50 (2009) to 60 bushels per acre (2022). If those rates of increase remain the same, projected yields in 2025 are 209 for corn and 62 for soybean; by 2035, projections are 235 bushels for corn and 69 bushels per acre for soybeans. If we remove the “outlier” year 2012, the corn trendline pops up, to predict yield of 213 bushels in 2025 and 240 bushels in 2035.