High Yield with Less Rainfall: Corn and Soybean in Illinois in 2022

Every crop year brings its own set of challenges during the growing season. The story of the 2022 growing season in Illinois was one of dry weather and crop stress at times and in some places, but good to great yields anyway. How did this happen?

Growing season weather and crop conditions

April was not a wet month, but it was wet enough and cool enough to delay planting; by May 1, only 7 percent of the corn and 5% of the soybean crops were planted. With cool temperatures and above-normal rainfall the last week of April, some of those struggled to emerge. Despite the slow start, planting progress accelerated in response to warm, dry weather in May, and by May 22, 78% of corn and 62% of soybean crops were planted, both close to the 5-year average planting progress. The 5-year average does include 2019, with its historically slow start to planting.

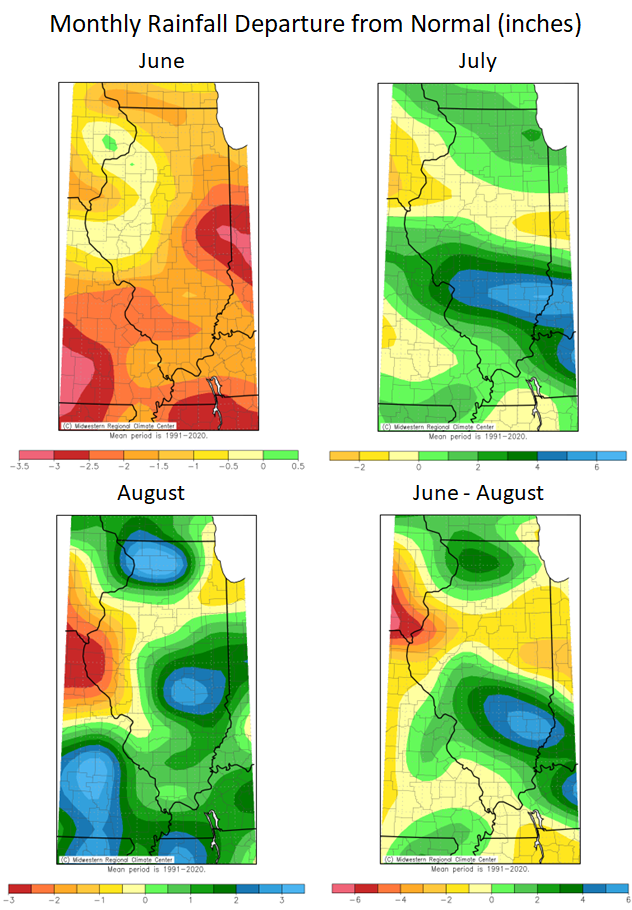

The weather pattern during the summer was not uniform across Illinois (Figure 1). June was remarkably dry, with rainfall deficits ranging from a half inch in west-central Illinois to 3.5 inches in east-central Illinois: less than an inch of rain fell in some places. July brought drought stress-relieving rainfall to most areas. Still, rains did not come uniformly: northern Illinois got some in the first week, central Illinois in the second week, and southern Illinois in the third and further weeks, including some high amounts of rain in southeastern and southwestern Illinois.

Although crop conditions scores rose into the 70% good + excellent range following July rains, early-planted corn began to pollinate, and soybeans began to set flowers, before the rains arrived in some areas. Where rainfall came a week or two after the start of corn pollination, the delay caused early-planted corn to show more “tip-back” with kernels not developing on some length of cob at the ear tip. This was mostly the result of kernel abortion, which is the failure of kernels – starting at the tip of the ear where sugars are in lower supply – to fill after being fertilized.

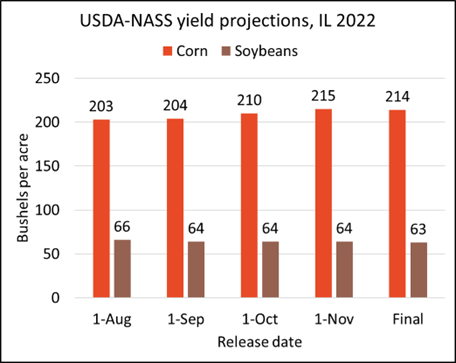

Rainfall in August varied across the state, but amounts were closer to normal than in previous months. Both corn and soybean had good canopy cover and color as the crops began the rapid seed-filling stages in August. In the case of corn, the USDA-NASS yield projections increased from 203 bushels per acre in August to 215 bushels per acre in November, with the final (January) yield of dropped 214 bu/acre (Figure 2) – a new state record. Soybean yield projections went down 2 bushels per acre from August to September, remained at 64 bushels per acre until November, and dropped another bushel to produce a final yield of 63 bushels per acre.

Why did corn yield relatively better than soybean?

Most producers, especially those in areas with stress before and during pollination, were pleased – if not astonished – by the high to very high corn yields they harvested in 2022. As discussed in an earlier article (Nafziger, 2022), the above-normal kernel weight was a key contributor to high yields in 2022. We believe that kernel numbers were somewhat lower than normal in such fields, but that having healthy canopies with dark green leaves up to physiological maturity helped these kernels to fill to a larger size than normal. We usually use 80,000 kernels per bushel as the default value when we estimate yields based on kernel counts before kernels are filled. In some fields in 2022, kernel size was likely at 70,000 kernels per bushel, and maybe more. At 34,000 ears per acre and 500 kernels per ear (17 million kernels), 80,000 kernels calculates to a yield of 212.5 bushels, while 70,000 kernels per bushel produces a yield of 242.9 bushels per acre. Larger than normal kernels probably contributed to the increase in yield reported by NASS from August to later estimates (Figure 2). Although corn grain dried slowly, probably due to sugars in the kernel (Nafziger, 2022), September and October were relatively dry, and grain quality was generally good to excellent.

Why did soybean not yield, at least relative to expectations, as well as corn in 2022? Soybean was planted a little earlier than normal, and like corn, the crop benefitted from good stands, lack of damage from standing water, and low levels of soilborne and foliar diseases. The beginning of soybean flowering was delayed by more than a week, and both flowering progress and podsetting were slowed as well, we think by stress; plants in late July were still short, and canopy cover was not very complete. Rainfall after that resulted in the addition of more nodes with flowers, but leaves at these nodes were not able to support pod formation and seedfilling as well as they would have if they had formed earlier. Figure 3 was taken on August 12, and shows that pods on the upper part of the plant had not yet begun to fill.

Temperature and moisture conditions were favorable for filling soybean pods, but we believe that the late start to pod-filling, along with lowered pod numbers, combined to limit seed number per acre. Seed size was normal or a little larger than normal, but couldn’t make up for lower seed numbers. Most producers reported that soybean yields were “good, not great,” and the 63-bushel state yield, while only a bushel less than the highest on record (in 2021), reflects this. So we’ll take it with thanks to Illinois soils, which maintained very good soybean yield levels despite the stresses in 2022.

What does 2022 tell us regarding the relative drought tolerance of corn compared to soybean? This is a much-debated topic, with 2022 showing that, under certain conditions, corn might have an advantage. When it’s dry early and remains very dry through most of July, with rain returning in late July (this was the pattern in 2012), we see the opposite – corn yields very low compared to soybean yields. The worst year for soybean relative to corn in Illinois was 2003, when corn yielded 164 and soybean only 37 bushels per acre. The weather that year was not very unusual, but soybean plants grew tall with heavy canopies and lowered pod numbers, which limited yields. The flowering and seed-setting stages of soybean last considerably longer than the equivalent period (pollination) in corn, which can often help it recover from dry conditions when rain flows, but patterns of dryness can also favor corn. Genetic improvement has made both crops more productive under a wide range of growing conditions, including periods of dryness.

Crop yield trends in Illinois

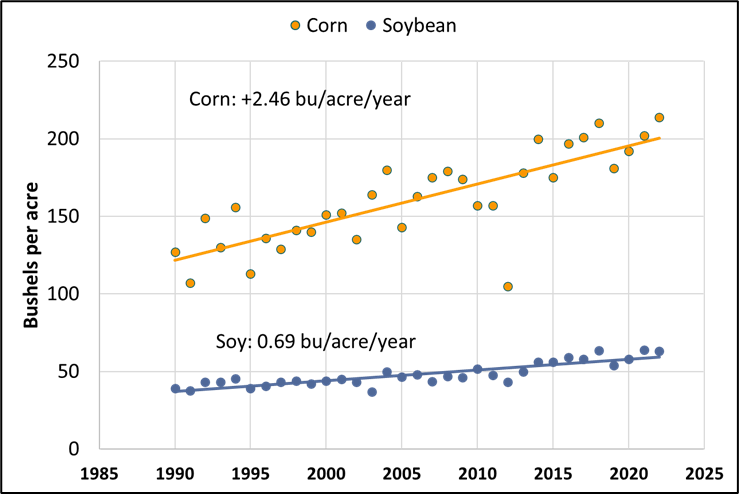

Figure 4 below shows the yield trends for corn and soybeans in Illinois from 1990 through 2022. Both trendlines are linear, although there is a hint of yield acceleration for both crops. Corn yields have increased by 2.46 bushels per acre per year over that period, while soybean yields increased by 0.69 bushels per acre per year. The data over this period produced trendline yields, by 2022, of 200 bushels per acre for corn and 59 bushels per acre for soybeans. If those rates of increase hold steady, Illinois corn and soybean yields will be 269 and 78 bushels per acre, respectively, by 2050.