Considerations for fall application of anhydrous ammonia

You can also read this article in Portuguese

With warm weather prevailing through most of September and dry conditions through mid-October, corn and soybean harvest in Illinois has progressed well, with 49% of the corn crop and 62% of the soybean crop harvested by October 13, compared to 5-year averages of 44% for corn and 47% for soybeans. September rainfall was 1 to 3 inches below normal, and hardly any rain has fallen so far in October; the October 15 drought map shows 69% of the state in abnormally dry to severe drought conditions. Temperature in the first half of October averaged about 6 degrees above normal, before falling this week, with the first frost on October 16 or October 17 over most of Illinois. That is relatively early for the first frost in southern Illinois but not for northern Illinois.

The early harvest and dry conditions are prompting many producers and dealers to start considering fall nitrogen fertilizer applications. Applying anhydrous ammonia in the fall is common in Illinois for several reasons. A primary reason is price — ammonia is historically cheaper in the fall than in the spring, although this difference has become less consistent. Some farmers apply ammonia with other fall operations, such as strip-tillage, which reduces the application cost. Soil conditions are typically better for application in the fall than in the spring, when wet weather can delay ammonia application, which can delay planting or push application to after planting. Applying ammonia in the fall also allows farmers to spread out their workload, leaving more time to focus on corn planting in the spring.

There are also drawbacks to fall application. Nitrogen applied in the fall is not used until the growing season begins, making it vulnerable to losses through leaching or denitrification for six months or longer. Studies in Illinois and other Corn Belt states have shown greater potential for N losses following fall N application, especially with mild winters and wet springs. Although N fertilizer prices have come down some, lower corn prices have kept fertilizer N costs high as a proportion of direct costs. It’s important to protect this investment.

What happens when anhydrous ammonia is injected into the soil?

Ammonia reacts with water:

NH3 + H2O —> NH4+ + OH–

When injected into the soil, anhydrous ammonia (NH3) gas reacts with water to form ammonium (NH4+) and hydroxide (OH–). The ammonium ion is positively charged and binds to the negative charges of clay particles and organic matter. As long as the N stays in the ammonium form, N losses by leaching and denitrification are not substantial. Only when ammonium is converted to nitrate (NO3–) via the nitrification process can the applied N be lost. Nitrate has a negative charge, and so is not held by clay particles and organic matter; thus, it moves freely with water. In other words, applying N as ammonia and keeping it as ammonium as long as possible in the soil minimizes N loss potential.

Biological nitrification:

1) 2NH4+ + 3O2 ↔ 2NO2– + 2H2O + 4H+ then

2) 2NO2– + O2 ↔ 2NO3–

The nitrification process, carried out by specific soil microbes, is influenced by factors like soil pH, temperature, moisture, and ammonium levels. A temporary increase in pH from the reaction between ammonia and water can (temporarily) inhibit nitrifying bacteria in the retention zone. The resulting hydrogen ions (H+) from the first step of nitrification will cause soil pH to eventually decrease, often to less than the original pH. Nitrification will gradually increase again if soil temperatures allow the microbial population to rebound post-application. While nitrification doesn’t stop until soil temperatures reach freezing (32°F), it slows significantly below 50°F. The nitrification rate varies with temperature, being around the maximum rate in the upper 70s and 20% of the maximum rate at 50°F. Thus, delaying application until soil temperatures are 50°F or less can ensure that most of the applied N enters the winter as ammonium, and over-winter losses of the applied N will be minimal as long as soil temperatures remain low.

Another way to slow nitrification is to use a nitrification inhibitor, particularly when soil temperatures fluctuate after application. These inhibitors decrease the activity of nitrifying bacteria (either by killing the bacteria or by chemically inhibiting their ability to convert ammonium to nitrate). The most common inhibitor in use over the past decades is nitrapyrin, known commonly by its Corteva trade name N-Serve®. Centuro®, with the active ingredient pronitidine, is a relatively new nitrification inhibitor from Koch Agronomic Services.

When should fall N be applied?

Our recommendation for fall ammonia application in Illinois is to wait until soil temperatures are below 50°F and use a nitrification inhibitor. While it would be ideal to wait for soil temperatures to reach 40°F or lower – since nitrification rates are at less than 5% of maximum at that point – this is not always practical in northern and central Illinois, where such temperatures are reached only by mid-November or later. Waiting until then would significantly shorten the window for fall ammonia applications.

To manage the risk of significant nitrification after applying fall nitrogen, it’s essential to consider both current and forecasted soil temperatures when determining the timing of the application. Since soil temperatures can vary throughout the day and differ at various depths, we must also decide when and where to measure soil temperature. The degree of temperature fluctuation depends on factors like soil texture and color, moisture levels, air temperature, and sunlight exposure. Instead of using extreme values, we typically measure soil temperature at 10 AM and at a depth of 4 inches in bare soil to estimate average daily conditions in the ammonia band following application.

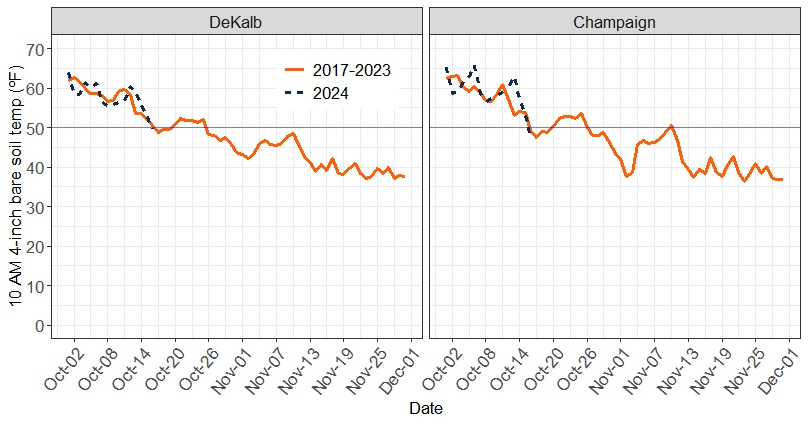

Figure 1 shows soil temperatures at DeKalb and Champaign averaged over five years (2019-2023) and so far in 2024. It’s not unusual for soil temperature to drop below 50°F in October, but it tends to increase after that, and often settles below 50°F only after the first week in November. Soil temperatures in October 2024 have been close to the 5-year average. The weather forecast is for high temperatures to remain mostly in the 70s through the end of October, so we probably won’t see soil temperatures staying below 50 degrees until sometime in November.

Are soils too dry to apply anhydrous ammonia?

Soil moisture is needed to dissolve ammonia, and also for maintaining conditions that allow sealing of the injection slot. If soils are too dry and cloddy, they may not retain ammonia gas well. In recent years some have tilled dry soils before fall application in order to break up compaction and improve placement. That is being done this year as well. Surface soils are probably crumbly enough to seal after application, and there may be enough water at application depth to retain the ammonia. The real question is whether or not ammonia knives can be run deep enough for proper ammonia placement. The only way to know is to try running the applicator. If it can’t get to the proper depth, tilling to try to loosen the soil may be difficult as well, or at least costly in terms of fuel and equipment. Waiting until next spring is an option in most cases. Fall tillage after soybean harvest leaves little residue cover, which raises the risk of soil loss and of blowing soil that can reduce visibility.

Final considerations

If you plan to apply anhydrous ammonia this fall, keep these conditions in mind to minimize N losses:

- Avoid application south of IL Route 16: In southern Illinois, soil temperatures are generally not cold enough consistently during the winter to prevent nitrification, and soils warm up early in the spring, increasing the chances of loss.

- Avoid application to heavy- or coarse-textured soils: Do not apply fall ammonia on very fine-textured soils (like clay or silty clay) due to the higher risk of nitrogen loss from saturation and denitrification next spring. Similarly, coarse-textured soils (sand or sandy loam) should be avoided due to the increased risk of nitrogen leaching.

- Wait for soil temperatures to fall below 50°F: Apply ammonia only when soil temperatures at a 4-inch depth at 10 AM (under “hourly” data) are below 50°F; the colder, the better. While you can check temperatures on websites like the Illinois State Water Survey, you might measure soil temperatures directly in a field before application, and take into account the temperature forecast in the coming days.

- Use a nitrification inhibitor: This can help delay the conversion of ammonium to nitrate, reducing potential nitrogen losses.

- Ensure proper soil moisture for sealing: Make sure soils are neither too dry nor too wet to achieve proper sealing when applying ammonia at the desired depth – usually 6 to 8 inches. If you see white “smoke” escaping from the injection slot, ammonia is being lost, and adjustments are needed.

- Adjust N application rates for other sources: if you plan to apply other forms of N ‒ such as MAP or DAP this fall or next spring, planter-applied N next spring, or N solution as a herbicide carrier ‒ adjust the amount of fall-applied ammonia accordingly to meet the total N needs for next year’s crop. The Corn N Rate Calculator provides optimum N rates (see Table 1 below) for corn following corn or soybeans in northern and central IL.

- Be Safe: Anhydrous ammonia is toxic to humans and other living things, and needs to be handled with great caution. Be sure to follow all available guidance on keeping equipment and operations safe.